Ep 5: Remediation

A fence blocks access to the former town site of Uravan, located along CO Highway 141.

After Uravan closed and was set for demolition, its residents were forced to scatter elsewhere. Today, its nearby baseball park hosts an annual picnic for former townies who refuse to let the last memories of Uravan die out. In an interview with EPA superfund officials, we learn the philosophy of cleanup that led to the remediation of Uravan and its current status. Close by, a new uranium boom refuses to let the dust settle for long.

Episode Transcript

Alec Cowan: 150 million years ago, geologists say Western Colorado was covered in water and mud.

Archive Footage: To find the petrified river and its uranium, a man must understand its origin.

Alec Cowan: Rivers and streams deposited shale and volcanic ash, trapping plants and dinosaurs in layers of sedimentary rock. This expansive region of orange and red bluffs, arches, and canyons is still one of the most impressive regions in the world for finding dinosaur fossils.

Archive Footage: For a thousand miles, sand dunes circled its shores. Then, as the centuries passed, the west slowly rose, and the sea retreated.

Alec Cowan: But that isn't all. The acidic water mixed with the organic fossils, creating a collage of coffinite, vanadium and uraninite near present-day Naturita, Colorado. This resulted in massive ore deposits containing millions of tons of uranium.

Archive Footage: At one time, the whole West buckled and the earth spewed forth fire.

From deep within the earth's crust, hot solutions bubbled up bearing uranium.

Alec Cowan: By 1912, a small band of miners hunting for radium started the Joe Jr. Camp, the eventual foundation of a town whose sole purpose was mining that ore: Uravan.

For this region of Colorado, with its rugged rock mesas and open valleys filled with cattle, uranium changed everything. It brought new workers to new towns, provided a lucrative, if a little unstable, employment. And when Uravan was closed in 1988, after the mid-century rush, its residents spread elsewhere — back home out of state, or downriver in Colorado.

For most people driving by the site today, Uravan is little more than a name on a road sign, another blip on this canyon land's geologic history. And that's what I thought when I first heard about it as a kid. It was just another rural Colorado legend.

But the town itself is still there, just buried in a large stone repository. For some, it's a sign of the region's toxic past and the ongoing struggle to clean it. But this area still holds a lot of memories for those who once called this Colorado valley home.

And for this unique region of the country, which is still rich with uranium, the way Uravan is remembered is as much about the future as it is about the past.

Jane Thompson: We're the generation of kids that got to grow up, but we're not the workers. It's, it'll be gone. It'll be done. There weren't environmental laws

Frances Costanzi: back then. So, we end up cleaning them up.

Dr. John Boice: Are the billions of dollars for cleanup well spent, in terms of the health protection? And so that, that's the ongoing debate.

Alec Cowan: I'm Alec Cowan, and this is Boom Town: A Uranium Story.

Episode 5: Remediation.

Highway 141 just outside Gateway, CO, with Utah’s La Sal Mountains in the distance.

Pt. 1: Canyon Country

Alec Cowan: I have to be honest — growing up in Colorado, you take the natural grandeur for granted. I live in Seattle now for work, and thanks to sites like Hanford, the nuclear legacy of the area feels front and center. But in Colorado, I knew nothing about my hometown's history with uranium. It's easily lost in the hiking and biking, the craft breweries, the trendy eateries.

But as I drive toward Nucla, through the canyons farther south from my hometown, the history is front and center. Passing through Gateway, along Highway 141, the old uranium mill is still in the center of town. As I drive, I pass by the old Uravan site, which has a roadside pull-off and a small information kiosk.

30 minutes south in Naturita, where I'm staying for a few days, it only takes about 10 minutes to walk from one end of Main Street to the other. I stopped by a vintage sign, straight out of the 1950s, for something called the “Uranium Drive In.” It doesn't run anymore, but for a long time, this drive-in was the only place to see movies in the area, and it's one of the only landmarks in town.

These are places where the elevation easily overshoots the population by a few thousand, and I know that despite my attempts at not looking like a city boy, I'm sticking out like a sore thumb.

Jane Thompson: You look like an Alec.

You look like Jane.

Alec Cowan: In fact, that's how Jane Thompson easily spots me, waiting on a park bench, a little early for our interview in Nucla, a sister down just down the road.

Jane Thompson: It's, um, it's funny because when somebody different is sitting on Main Street, we notice right away.

Alec Cowan: I uh, yeah. I figured I was getting some looks.

Alec Cowan: Almost every person I spoke with said that if I talked to anyone, it had to be Jane. Together, she and her sister Sharon help preserve regional history as part of the Rimrocker Historical Society.

They're also third-generation Uravanians.

Door opens.

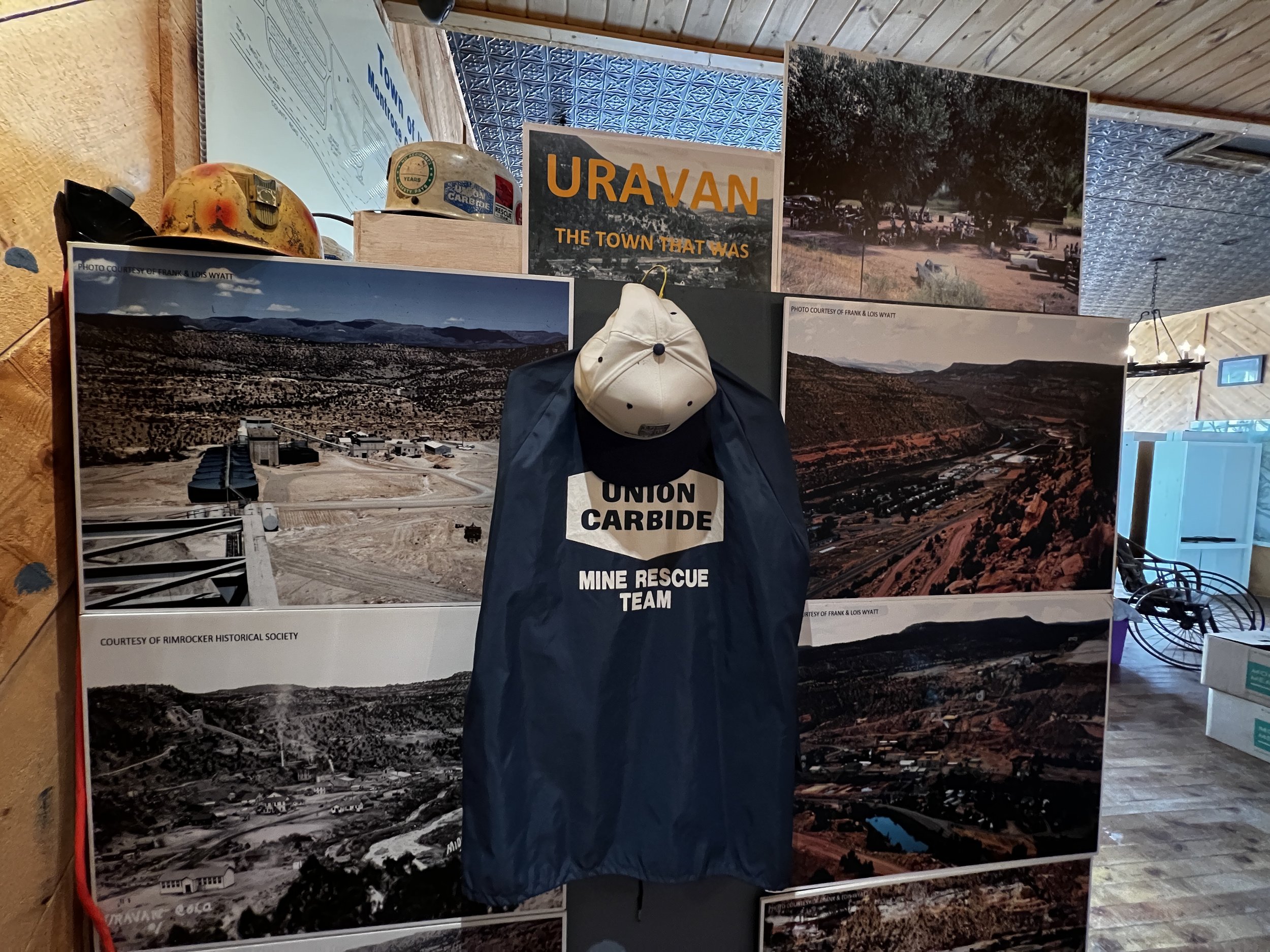

Jane's leading me into a purple and lime green storefront. This is the site in progress for the Rimrocker's museum dedicated to towns like Uravan. The museum as it stands now is modest: just one big room in what feels like an old western-styled timber house. But as Jane shows me around, one thing quickly catches my eye. A thick jar with something yellow inside.

Is this uranium? Is this actually? Uh huh,

Jane Thompson: yeah, this is uranium. This is a nice chunk of uranium ore. We'll turn on our little Geiger counter, and you can hear it kind of tick. And then, you know, you move it away, and it stop ticking, and come back over here.

Alec Cowan: After months of hearing people talk about uranium, this feels like a big deal — at least to me. Jane's pretty nonchalant about the whole thing. Yet again, I'm showing just how much of an out of towner I really am.

Jane Thompson: You know, people, everybody has a different response. So, um, I've, I actually have had one lady absolutely run out of the museum and not come back.

Alec Cowan: The Rimrockers collection is filled with typical mining implements. Things like drill heads, metal stakes — collection buckets that let you read the potency of the ore you were hauling.

When the writing was on the wall, remediation on the horizon, people began taking anything, any way they could. Jane told me the story of a worker who took bricks from buildings one at a time, smuggling them in his lunchbox day by day. Residents felt like everything in town was going underground, and so a network came together to preserve whatever they could.

More often than not, those items make their way to Jane.

Jane Thompson: There really is very little left from Uravan, and people kind of whisper it. I have the phone. From the lab. I'm gonna give it to you.You know, or I have a picture I'm gonna give to you.

Pictured above is the Rimrocker’s new museum in Nucla, CO, with materials from their collection, as well as the Uranium Drive-In sign and a mural from the local school in Naturita.

Alec Cowan: So let me more formally introduce you to the Thompsons. The Thompson saga began when Jane's parents moved from the nearby town of Norwood to Uravan.

Jane Thompson: My dad came in to work at the mill in Uravan and, my mom had just graduated from high school and they ended up getting married... and they were the second to the last to leave Uravan.

Alec Cowan: Both Jane and her sister Sharon grew up in town, but they later left to chart their own courses in California. It wasn't until 20 years later that Jane came back, and by then, Uravan was mostly gone. Her parents told her remediation started with radiation meters in their homes. The ones with the highest readings were the first to go.

Progressively, the slice of life that was Uravan began to slip away, and Jane said it was devastating to those who'd spent generations in town.

Jane Thompson: They couldn't plant their gardens anymore, and they couldn't eat the fruit off of the fruit trees. And my mother always grew the best gardens and she had the prettiest flowers in town, and it just didn't make sense. She was in her 50s and she had lived there since she was four years old, and to be told that she couldn't eat her own food anymore ,just made no sense to her.

Alec Cowan: A lot of older residents wanted to keep their jobs to get a better retirement package. So they asked to stay as long as possible, or at least be transferred to another Union Carbide facility. Some folks took their severance, packed up, and left.

Jane's parents ended up just south in Paradox, with a few mementos of their own.Things like their flower bushes, which her mom personally pulled up and trucked out of town.

But without a home to return to, Jane and Sharon ended up in Nucla, where they live today.

Jane Thompson: My dad passed while I was gone. My grandparents passed. I missed a lot of things. The people that stayed had to go through all that. So we were kind of the outsiders that deserted them, you know, that didn't stay for the long term. For the long haul.

Alec Cowan: Jane's work on preserving Uravan's history is a bit of making up for lost time. And being the town's most outward-facing champion comes with some loaded responsibilities. She said there seems to be an assumption that everyone from Uravan is somehow sick or dead from their exposure to uranium.

After all, the town was dangerous enough for it to be buried underground, right?

She actually cut a joke about that, saying she opens up her local history presentations by saying 1. I'm not sick, and 2. I do glow in the dark.

But that humor doesn't mean she ignores Uravan’s more sinister reputation. She acknowledges that her grandfather died from working in the mines. And there were definitely problems with how much radioactive waste was in need of cleanup.

As difficult as remediation was, residents understood that it was the company's decision on what to do, and that cleanup was the path they chose. But with the town gone, so goes the on-site history — and the complexity of Uravan's story.

From Jane's point of view, without the town, the fear is all that's left.

Jane Thompson: Well, it was a company town. Everybody has the right to do whatever they want with their property. And it was going to happen. I mean, you look at the pictures of the acid ponds on the river. I had people that worked there that said we should have just, everything should have been gone.

But there were a lot of people still that worked for the company, and then people here that felt like we needed to preserve that mining history and the history of what happened there. I mean, honestly, Uravan, from the radium that went to Marie Curie, to the Manhattan Project, to the Cold War — touched our national history in many ways. And to just wipe that town away and, and let's not talk about that history anymore, it's gone, it's done, it didn't… was wrong.

But what, what I, what I am perplexed about is that their parents, who grew up here, They'll look at me and they'll say, why don't I know this? How did I go all the way through school, and never hear about Uravan?

That history was lost to our community.

Alec Cowan: After an hour of chatting with Jane, her sister Sharon comes in.

The two are leaving to set up for a gathering at Uravan’s old baseball park. That's the one plot the historical society has been able to carve out. So I leave them be, and get directions for tomorrow's picnic. In the meantime, I walk into almost every business in Naturita, bringing up uranium as I can.

Most folks know a little, but nobody really knows a lot. Inevitably, I end up getting pointed back to Jane, who I'm starting to think is a town celebrity.

By the evening of my first full day in Naturita, I'm sitting on the porch of my hotel, enjoying some towering clouds over the Uncompahgre Plateau. Tomorrow, along with pilgrims from all over the country, I'm going to see Uravan.

That's after the break.

The towns of Nucla and Naturita, Colorado are a 10 minute drive from one another. Many residents who used to live in Uravan have relocated to these two small towns.

Pt. 2: Radioactive Materials

Alec Cowan: The Uravan site is about half an hour north of Naturita.

The road winds along the San Miguel River, passing pastures with cattle, and the occasional stand of cottonwood trees. Today's picnic will be at the old Uravan Baseball Park, which has since turned into a small campground. Because the baseball park was a little farther south of town, it wasn't heavily exposed to any uranium products, so it's fair game for recreation.

This morning, Jane is busy directing vehicles for the annual Uravan picnic. Once a year, the Rimrockers organize a get-together, and folks drive out from across the country. It's a hot August day, and as visitors trickle in, I set up on a corner bench with my microphone. Despite the weight of their loss, these former residents haven't lost their sense of humor.

T-shirts read: “Caution, I lived in Uravan, radioactive materials,” or “Uravan: Population 0.”

I’m sure you won’t be surprised to hear that they all glow in the dark.

Emily Latimer: Okay, my name is Emily Latimer, and I lived there 17 years.

Alec Cowan: At the Latimer table, I chat with Emily, her husband Joe, and her daughter, Cindy. They live outside Kingman, Arizona, an 8-12 hour drive, depending on how often you stop.

Emily Latimer: Really, I enjoyed living here. I really miss it.

Alec Cowan: Why'd you, why'd you move away?

Emily Latimer: The job. We no longer had a job.

Alec Cowan: While most of my previous interviews were about the ins and outs of work in the mines, or the caution around uranium, this conversation feels like we're talking about an old, black-and-white TV show. Emily tells me about spaghetti potlucks on B Block, a Mr. Haney who worked at the drugstore. Things like swimming lessons, and the rare snow day. I hear a familiar nonchalance about being around uranium.

Emily Latimer: You know, I never even thought about it. Now, I do realize there were people that had lung problems or whatever, but, um, I never was afraid of it. To me, if it's gonna happen, it's gonna happen. You can't stop it anyway. So, don't run away from it.

Alec Cowan: When I asked this question, if she was worried about uranium, Emily's daughter Cindy rolls her eyes. She's embraced the uranium stigma.

Cindy Latimer: My sister and I would actually eat yellow cake.

Like actual uranium yellow cake?

Yeah, yeah. We, we, uh, my sister and I would wait until the rainstorms and then we'd rub it all over ourselves and then we'd start licking it because it has that metallic taste to it. Yeah, now I'm older and going, well that probably was not the smartest thing in the world.

Alec Cowan: As I chat with more people. I hear familiar stories from different angles. I'm regaled with high school stories by two sisters, Bette and Jean, who keep filling in the gaps of each other's memories.

Bette Nickell: Down at the river, there was streaks of kind of an orange, and I just thought we'd moved to a fairyland. It was tailings from the river… not good for the people downstream.

Jean Nyland: Back then, that was some of the dirtiest jobs that they put the college kids in. You know, they worked during Thanksgiving, vacation, Christmas, all summer long.

Alec Cowan: But these conversations aren't all happy memories. I spoke with Don Colcord, a pharmacist who stayed in Naturita since the town was closed. Don was a mill worker himself before leaving for college. And he laments the loss of the industry and the town, what it did to the region.

Don Colcord: Well yeah, the mines closed, the mill closed, and so people were moving away, they had no jobs and everything. It was, it was a pretty tumultuous time. I was on the school board at the time, and we went from 600 kids to 300 kids in like 3 months.

Alec Cowan: These annual picnics are meant for celebration, but inevitably, conversations turn to questions of what they miss most, and what they'll never be able to see again. Did you work in the mill? Who was your fifth-grade teacher? How's your dad? And most of those I spoke to had plans to drive by the site, a dusty and hot drive by memory lane.

After a heaping of barbecue, Jane announces that it’s time to begin cutting the “yellow cake.” Yes, a yellow sheet cake with yellow frosting to make it look like a block of concentrated uranium.

As for me, I decided it's time for me to head out and see the actual site up close. Jane is busy with the picnic, so I'm left to drive up on my own.

Numerous signs from the county say it's illegal to mine in the area. I guess they don't want anyone trying to strike it rich like they used to.

In fact, I see an old cave just across the road from the site, but it's closed by a huge metal door and signs saying ‘keep out.’

Door close

Alec Cowan: It doesn't sound too exciting standing where I am, but that's kind of the point.

I'm staring out over a wide plain of dirt, and aside from the barbed wire fence, there's no trace that anyone ever lived here. In front of me is a bright yellow sign saying, quote, Any area or container on this property may contain radioactive materials.

I wonder if Jane's Geiger counter from the museum would pick anything up. I jump back into the car, and follow a gravel road binding to the top of the sandstone mesa. At the top of this hill is where the B Plant would have been, the second of Uravan's uranium mills. Again, there's no sign of human life except for some tire tracks that briefly cut into the dirt, and more of those yellow signs cautioning radioactivity.

But a little farther up the road is something incredible, and it's difficult to find the words to describe it. Because so much of the material in Uravan was radioactive, it wasn't sent to some local landfill. All of it was trucked to the top of this hill where it was buried in an excavated repository.

It's at least the size of a full football field and includes a mix of what must be thousands of light and dark stones. I can't emphasize enough just how massive this repository is in person. It's like looking at a carefully planned zen garden. And with the mountains in the distance, I have to admit, there's kind of a beauty to it.

Frances Costanzi: I think my first impressions were, since the cleanup was done, was more how beautiful the area is.

Alec Cowan: Fran Costanzi is a Senior Remedial Project Manager with the Environmental Protection Agency.

Frances Costanzi: I had the site transitioned to me sometime back in 2009.

So that was after the cleanup was substantially completed.

Alec Cowan: At this point, Fran is one of the longest-tenured superfund officials with experience working with the Uravan site. And even getting to talk with her involved weeks of bouncing back and forth between local and federal agencies. In total, there are a handful of state, private, and federal oversight layers in charge of Uravan’s cleanup. As far as nuclear cleanup sites go, that makes it a bit of a unicorn.

But let's get back to that giant pile of rocks. What's going on with that?

Frances Costanzi: It's a combination of barriers and also that very thick and noticeable stone cover that you saw. It would make it very difficult for someone to inadvertently dig through and somehow come in contact with radioactive material.

And then there's scanning that's done to make sure that radiation levels on the surface don't exceed a certain level so that the radiation is contained in those areas. There's also controls to direct water away from the site to keep it, you know, relatively dry. And that's all a part of the design standards that are done to meet the nuclear regulatory criteria.

Standards for repositories like this, so that they will last for a very long time, because that's how long radioactive material remains a concern.

Alec Cowan: As I've mentioned before, throughout the decades, there have been numerous studies investigating the potency of radioactivity in uranium towns; but ask anyone in this part of the state about Uravan, and you're sure to hear about the pollution and dangers of uranium. So I wanted to get as close as I could to Uravan's cleanup situation on the ground.

And Fran didn't really give me a detailed breakdown as to what went into this pile, or what the EPA calls the “remediation site.” And at this point, folks at the EPA told me there isn't anyone at the agency today who worked on Uravan from that long ago.

So for the history of the site's remediation, they pointed me towards two documents: a 111 page Final Remedial Investigation Report, and the 101 page Site-Wide Record of Decision…

…and here is what officials found.

Remediation started with a lawsuit brought against Union Carbide by the State of Colorado. Basically, the state was using federal environmental laws to compel the company into cleaning up its pollution. From there, the Department of Health entered into what's called a “consent decree” with a Union Carbide subsidiary called UMETCO.

Together, these two parties agreed on the long term plan for who would be in charge of the on the ground cleanup work. That's where the EPA comes in. They set the standards for how clean the final site needs to be and monitor the work done by those state and local parties in the agreement.

Now, in order to determine what kind of cleanup needed to be done, the agency used two main categories for measurement: the natural background levels of the area and the radiation levels once mining took place in those same areas. For the latter, the EPA's risk standard is at or above a one in a million chance of developing cancer. The report points out that as far as risk range goes, that's actually on the low scale of risk.

Once the parties tasked with cleanup began taking measurements, they found the areas with the highest radiation levels were the bee plant, the local dump, and the county road leading to the top of the mesa — the one I just drove on. In these places, some of their measurements were close to double that one in a million threshold. In addition, they found several hundred million groundwater and local river, which had to be extracted and evaporated. On top of that, they weren't only cleaning up elements like uranium and radium — they also found arsenic and ammonia, which are toxic to both humans and wildlife.

But that said, there were areas of Uravan that didn't require remediation.

Several patches of town were already at or below those natural background levels, including the E and F housing blocks, the gym area, and the ballpark. Basically, the risk levels here were already safe enough for humans. Of course, uranium was found everywhere, with small amounts in some places and high amounts elsewhere.

The interesting thing is that the B plant, not the A plant, was where the biggest problems were located. That was the mill on top of the hill, farther from town. I'm not sure if that was intentional on the company's part, or not. But regardless of how close or far the levels were, over 260 buildings were removed from Uravan and buried here, on what's called Club Mesa.

The top layer of soil from most of the town was basically scraped and reburied. Except for the wire fences, the land today is like no one lived there, both literally and radiologically speaking. The river and the air are clean.

So at this point, the job of the companies and agencies in charge of Uravan’s cleanup is just to make sure the solution is working as intended. Here's Angela Zachman, also with the EPA, discussing their federally required on the ground work with UMETCO.

Angela Zachman: So, the Uravan site has an O&M plan, or an operation maintenance plan, in place, and they monitor that site quarterly, annually, and after heavy rain events. We also, they also complete annual reports for us, and then we also look at the Uravan site every five years.

The stone repository atop Club Mesa, which contains over 260 buildings from the former town of Uravan.

Alec Cowan: Now, there is an important development in the works. Uravan is one of four sites in the nation with this complex web of uranium cleanup laws and array of agencies. Of those four, Uravan is the farthest along in cleanup, and it's set for something called legacy management in the near future. This officially takes the site off the state's hands, instead putting federal agencies in perpetual charge. It's basically a sign that cleanup is working as intended.

So if that's true, and the site is remediated enough to not be dangerous, I had to ask Fran — it's been 40 years. Is there any possibility that someone could live here again?

Frances Costanzi: There is some discussion going on now about some what we call reuse visioning or redevelopment visioning for the areas outside of that long term care area, such as perhaps the area down by the stream.

There may be a possibility of hiking trails, or perhaps a boat launch, or something like that could be possible in the future. I think residential is probably less likely at this point.

Alec Cowan: Less likely. Not exactly ideal for folks like Jane Thompson. But that said, Fran did recognize the significance of the site.

Not just for former Uravanians, but for U.S. history, too.

Frances Costanzi: Uravan is unique for many reasons, but often in communities, they often provided jobs, and in this case, people lived and worked in Uravan. I think that's an important part of their history. And certainly the Uravan site was an important part of the United States atomic history as well. So we're really aware of that as we go through the cleanups of the sites.

A lot of the sites did get contaminated, some of them quite seriously. For the most part, there weren't environmental laws back then. So, we end up cleaning them up. But we have an awareness of how the site kind of fit in the fabric of our history.

Alec Cowan: It doesn't seem like much, but after 40 years, I would have to guess that a hiking trail is better than nothing. It won't replace the luscious gardens that Jane Thompson's parents used to have, the historic boarding house, or the community hall. But after decades of being told the ground was too dangerous, too radioactive to even walk across, I don't know… even if it's a small gesture, it feels like a significant one.

And looking at the report, it feels like there's nuance here. Areas of town were in clear need of cleanup, posing a risk to people living there and the environment. But there were also parts of town that weren't toxic, allowing gatherings like the annual picnic.

So why does that perception matter? Of course, it probably goes without saying that, residential use aside, Uravan won't ever be used to mine uranium again. But what about in the canyons nearby?

A little bit of closure and a peek at the future, after the break.

Pt. 3: Revival

After $120 million in cleanup, it seems like the decades of work on Uravan are finally going to pay off. And considering the timescale of the nuclear world, where invisible particles can decay for hundreds to thousands of years, forty years to achieve success seems pretty triumphant.

According to historian John Findlay, the successes of cleanup are one piece of a long crusade to restore trust.

John Findlay: The success of World War II, the success of atomic bombs, are things that gave people confidence in the government. Look what the government did. It did this and this and this. They won the war. You get to the ‘60s and the ‘70s and you get your Vietnam, you get your Watergate. People do not trust government.

And that mood is what prevails as the United States government starts to take on the task of cleanup. Prove it to us. You know, look, look how we screwed this up, screwed this up, prove it to us.

Alec Cowan: But trust wasn't the only problem. At the close of the Cold War in the 1980s, the U.S. was signing agreements with Russia to stop testing weapons.

The nuclear stockpile wasn't growing, and the nuclear industry was tanking. As I've said before, that meant those who worked in the industry lost their jobs. moved away.

But for the Atomic Energy Commission, or the Department of Energy as it's called today, there was also a crisis going on.

John Findlay: And that entailed what was called a whole kind of culture change within the Department of Energy. They had to sort of figure out what they were going to be, and to maintain credibility, take cleanup seriously. If not, they would have lost some or all of their agency would have been farmed out to other organizations.

Alec Cowan: So in lieu of making nuclear weapons, cleanup became an industry unto itself. And as workers, downwinders, and local health departments began to bring lawsuits for their sicknesses, cleanup was also about liability.

Here's Dr. John Boice, who spent decades studying sickness in uranium towns.

Dr. John Boice: So, on one hand, unnecessary radiation should be avoided… but nobody lives in Uravan. So, okay, but maybe a hundred years from now, somebody will. But the radiation levels, even then, before the cleanup at this extremely low level, they would not be close to a level that you could detect health effects.

Alec Cowan: The central question I've been trying to get at in this series, isn't whether Uravan was or wasn't dangerous. There were clear issues, and so the question then becomes whether a community like Uravan should be able to choose that risk. Is there a scenario where the waste is reclaimed, maybe the town is downsized, and those who wanted to willingly live with that risk, no matter the scale — they could?

It sounds like a compromise, but throughout history, the fate of Uravan has always been in someone else's hands. The governments and the companies and that context makes cleanup about protection, sure, but it's also about liability.

Dr. John Boice: So here's the, uh, the issue, does the level of protection to the public… is it commiserate with the cost that society has to pay? And the argument, which is to me very reasonable, is maybe that's too much to pay for such a small level of perceived protection. And one should consider these regulations so that the cleanup levels are not so stringently low.

What happens with, with regulations, they assume a risk, say we can't allow one in a million, it's a regulation. We, the scientists cannot detect a risk at one in a million. And so, are the billions of dollars for cleanup well spent in terms of the health protection? And so that, that's the ongoing debate on how to balance this.

Alec Cowan: Regardless of how severe Uravan’s problems were, it met the bar for cleanup. And if you're a government agency, why wouldn't you set that bar low, and hedge on being more safe with radiation than sorry? I think as an everyday person, that's what I'd prefer.

But talking with Jane Thompson, I get the feeling that searching for compromise may never bring closure. And there's one particular situation, related to that liability, that's made it tough to let go. Toward the end of remediation, after most of the town was demolished, there were two buildings left standing: the historic rec hall and the boarding house. Jane Thompson and the Rimrockers were hopeful one of those buildings could be the museum they've now built in Nucla, the one I visited earlier.

They raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for renovations, and even managed to complete most all their work. The rec hall was even listed as a state historical building. But then, in 1999, custody of the land and the structures went to Dow Chemical. Jane says officials attended some historical preservation meetings, but in the end, they gave three days notice before they burned the structures, citing extensive mold and mildew.

The last residents who'd stayed in the area all gathered together to watch the fire from the road.

Here's Jane again.

Jane Thompson: We had this element of people. that lived in nearby towns who, um, just still just thought it was just horrendous that there had been such a place and that there was still such a place.

You know, there, they were just sure that if they came down here and, and went there, they were going to be sick. And I know I'm sure all it would take is one person to go in there and then feel bad afterwards and, and they would. And I, and I, and I know that, we know that, and we understand that, but it doesn't make it any easier.

Alec Cowan: When those two buildings were demolished, the last remnants of Uravan were officially gone. That set Jane and her sister on their current mission, to build the museum and tell the town's story however and wherever they can. Not to put too fine a point on it, but I guess you could call their work a kind of remediation in itself, one of history.

But it's a fragile one at that,

Jane Thompson: …you know, Sharon and I now are kind of the cheerleaders for Uravan. We're out there pushing and, and telling the story. Um, but someday we'll be gone. And, and we're the, we're the generation of kids that got to grow up there. Um, we're not the workers. It's, it'll be gone.

It'll be done. Um, and, and I don't know who will, I don't know that the story, the story will probably never be told with passion.

Alec Cowan: The loss of the physical town, regardless of the justifications, isn't just a downer for former residents. It's something I also heard from historian Michael Amundson. He teaches history of the American West and public history at Northern Arizona University.

And he says the question of how we preserve the nuclear past is one that many communities are facing.

Michael Amundson: I think every place is trying to, in some ways, explain its significance. Everything has a home of some famous person or something was done here. And Uravan has a legitimate claim to being part of the Manhattan project in World War II, and certainly part of the Atomic Energy Commission's programs of the fifties, sixties and seventies.

Unfortunately, most of those places are highly contaminated. It's like it was never there. It just, and I, I sort of hate to see that. And as a historian that does public history and preservation, without the built environment, without those things, we just don't, we do, we forget about it. When the last resident of Uravan dies off, there's not going to be anybody to tell the stories, except for historians. And that's a shame.

Alec Cowan: Okay. So at this point, I felt like I was at the end of Uravan’s story. I'd heard the history, explored the decision, found a piece of closure and some news about the future. With disaster after disaster, the uranium industry fell apart, and the boomtowns of the past had to face the music.

Regulations were ignored or non existent, and cleanup was one way for the government to make amends with its secrecy and recklessness. As for residents, their feelings are mixed. Some agree that it was for the best, the town needed to go. Others see it as short sighted or overcautious. But for those on the outside, Uravan is mostly a novelty, another quirky ghost town of Colorado's past.

And I have to admit, when I first started working on this project, that's what I thought, too.

Alec Cowan: Hey there, George, this is Alec over at, uh, uh, in Seattle again. How's it going?

But that's when I got in touch with George Glasier.

George Glasier: Can you talk now? Yeah, that's a good time for me.

Alec Cowan: George lives just outside of Nucla, where he runs a company called Western Uranium & Vanadium.

He says that while Uravan may be gone, the uranium certainly isn't.

George Glasier: We've got, we've got no doubt the best uranium vanadium mine probably in the world.

Alec Cowan: For decades, the uranium industry has been a ghost of what it once was. The U.S. can still siphon off its massive stockpile from the past. And that overstock, coupled with globally famous nuclear disasters and cheap foreign markets, meant there wasn't much of a reason to keep mining and milling in the U.S. And then there was cleanup, of course.

George Glasier: Uravan was obviously when they shut the mill down, they didn't need the town there, and so the companies just deemed it that the price wasn't gonna come back, so they just shut everything down. The US probably had 20, uh, processing plants through, you know, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico.

They're all gone. They're all torn down, virtually all of them.

Alec Cowan: …but a lot of time has passed. And in recent years, there just so happens to be a kind of renaissance in uranium. If you haven't heard, nuclear energy is making a comeback.

Trading footage: Front month uranium futures have traded up to 33. 50 per pound, gaining 38%. Investors see uranium as having potential.

You can see this article from Bloomberg. Hedge funds pile into uranium stocks set for dramatic rise. This is the most fundamental supply deficit of any commodity anywhere on the planet.

Uranium might be the most exciting macro investing story of the day.

Alec Cowan: George tells me uranium prices are the highest they've been in a decade. And so his company is trying to blow the trumpets, ring the bells. The region is back open for business, and his company has the minds and the determination to make it happen.

Well, can you tell me a little bit about the kind of. Mining operations that you have going on. I mean, how many plots stakes mines are we talking about here?

George Glasier: Well, the Sunday mine complex was actually a Union Carbide mine. It was owned by Union Carbide. So it's been in production off and on for years. There are actually five separate mines there, but we've mined in one of them. We're opening up three of the others very soon, but they're underground conventional uranium mines.

Just, you know, you go in and you drill and blast and you haul the ore out.

Alec Cowan: Today, opening a mine isn't as straightforward as it used to be. For example, on top of the expenses for buying and operating a mine, Colorado requires a bond for remediation up front. That means prospective miners are basically pre-paying for cleanup.

But the mines and permits are one thing. Because all the processing mills in the region are closed, George needs to build a completely new one. But George tells me he has a trick up his sleeve. Some new kind of technology that will revolutionize the uranium world.

George Glasier: Nobody except us is going to build a new processing plant right now in the United States.

We're the only one doing it. And we're doing it because we own a technology that makes the processing plant considerably smaller and the environmental footprint a lot smaller. So it'll be a lot, you know, but really bring the uranium industry back.

Alec Cowan: That news doesn't exist in a vacuum. The prospect of reopening local mills lives in the shadow of Uravan and its complicated booms and busts.

An industry rebound probably feels like good news for Uravan's historians who want to bring more attention to the area's legacy. More attention to those who took pride in their families’ sacrifices in the mines. But restarting the industry is less appealing for those who justifiably hold uranium in a negative light.

Those who saw the acid ponds and dirt clouds across the river, and had to wonder if uranium wasn't affecting their communities too. So if the industry comes back, will mines be more responsible? Can neighbors trust the cleanup? And can uranium really be safe? Those are questions I need to ask those who didn't live in Uravan.

And those are questions I can't answer with a quick phone call.

George Glasier: I'd be happy to give you any information, participate any way. We'd be happy to take you into the mine and show you what's going on.

Alec Cowan: I mean, what was I going to say? No?

——

Boom Town is recorded, written, produced, and scored by me, Alec Cowan. The guitar on this song is performed and recorded by my dad, Ron Hayes. And episode 6, the final episode of Boom Town, will be out soon.

George Glasier: We're working every day of the week, 12 hours a day. That's what the miners like to do. At a hundred dollars a pound, you know, you want to go as fast as you can.

Mike Rutter: We'll call the full face of oar. Just a huge chunk of, you can see where it comes down in the back.

Jennifer Thurston: I don't feel that we're prepared in any way to adequately protect the environment or to protect public health.

Recommended References:

Yellowcake Towns: Uranium Mining Communities in the American West (Michael Amundson)

Union Carbide to clean up uranium site in the West (New York Times)

Historic Uravan buildings go up in smoke (Montrose Daily Press)

Referenced Uravan cleanup reports:

Uravan Site-Wide Record of Decision

Uravan Final Remedial Investigation Report

Copyright Alec Cowan 2024